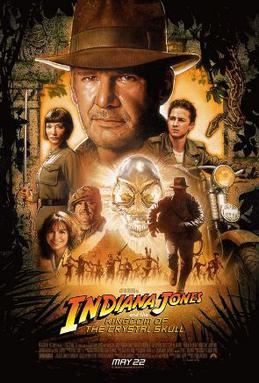

The cable guide actually labeled it Iron Man. Imagine my surprise when we started the DVR and found this instead. I can only surmise that we were fated to see Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of Nobody Really Cares About Making Good Movies Anymore.

This kind of thing only happens by accident.

So let’s pretend this is the McLaughlin Group — or better yet, The Sinatra Group — and take it point by point. Spoilers abound.

Issue 1 – The Title

William Goldman‘s most salient point about Hollywood — and there have been many — is: “Nobody knows anything.” Among the things “nobody knows” but are considered holy writ is: Titles Matter.

Exhibit A (through Z): Snakes on a Plane.

I realize that after one has masterminded a few modestly successful art films like Jaws, Star Wars, E.T., and Jurassic Park, one gets the freedom to take a little pass on the most basic tenets of story-telling, including the importance of title. But don’t. Please.

Contrast:

Raiders of the Lost Ark. A perfect stage-setting title. Not only does the word “raiders” scream action-adventure, it also gives a hint at Indy’s character: someone who plays by his own rules, a bit of a black sheep. “Ark” is a little non-specific — I thought it meant Noah’s ark — but “Lost” implies a search, the delightful cat-and-mouse game that comprises most of the second act.

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It’s a little hacky but this is a sequel. There’s no action word here, but riding the blockbuster success of the first film, all we really need to know is Indy’s back. “Doom” is a good word, telegraphing that this will be a darker film — which it was.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Again, points for letting us know Dr. Jones is back. “Crusade” is very good — an action-invoking word that carries a certain grandeur, implying an especially important adventure for Indy. I think adding “Last” was subtle genius because it hints at unfinished business, which turns out to be one of the major story lines of the film: the relationship between Indy and his father even more so than the continuation of the Crusades.

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. C-L-U-N-K-E-R. To begin with, not one single action word. Just the name of a place no one has ever heard of and non-suggestive of any concrete imagery. Imagery being the currency of film, the title is the first opportunity to start arranging a movie-goer’s expectations with some compelling — even if wildly inaccurate — images. “Kingdom” is such a nebulous idea it could mean anything from Buckingham Palace to Disneyland. You might as well call it Indiana Jones and the Bathroom is the Second Door on the Right. At least that would call up concrete visual imagery, however boring, for most of us. And as for “Crystal Skull,” the only image that popped into my head were those creepy Day of the Dead souvenirs you pick up in Mexico.

Issue 2 – The Intro

Leaving aside — for a moment only — all consideration of what is possible or plausible, I don’t get the beginning of this movie.

I have no problem with late point-of-attack openings. (In fact, I’m very prone to snip off the first scene or two of my own works when I realize I’m not getting to the “meat” quickly enough.) But in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of We Know They’re Villains Because They Wear Boring Gray Prison Jumpsuits, we get a mildly entertaining but pointless drag race sequence before the Commies take over an army base in Roswell, drag Indy out of the car trunk and start telling him what they’re going to force him to do against his will.

First, if you’re going to throw in a random drag race, why not have the teenagers actually be Soviets in disguise? I kept waiting for a girl in a ponytail and poodle skirt to lean over and cap the driver of the truck. That would have been cool. And a lot more likely than a fleet of army trucks filled with Russians speeding down a New Mexico road on a sunny afternoon.

Secondly, if Indy can’t instantly figure out why he’s been brought there and the baddies have to explain it to him, try again. Consider the opening of Temple of Doom: Indy faces off with an old foe and his actions, plus deft but minimal dialogue tell us all we need to know about the relationship, the stakes, what the characters want, etc. Explaining something to the audience is not the best way to begin a film but explaining anything to the main character at the outset is a disaster. Of all people, the titular character should know what is going on. 1

But instead, Indy is brought to Area 51 — a place he’s never been — to help retrieve a mysterious artifact he’s never really seen and can’t identify. “Even a blind squirrel gets a nut now and then,” doesn’t seem like the most reliable guiding principle for international espionage.

Instead of nabbing Indy, why not find the guy who boxed up the mysterious artifact and delivered it to warehouse in the first place? Maybe he tied some yarn on the handle so he could find it on the baggage carousel, who knows. The Russians somehow know Indy examined the top-secret artifact for the CIA and yet they can’t find one low-level grunt from shipping and receiving?

Issue 3 – The Villains

The main villain of this movie is Anna Wintour, played by Cate Blanchett, appearing in costumes recycled from 1980s Wendy’s commercials. She supposed to be “psychic” but her one attempt to read Indy’s mind fails — I guess she’s supposed to be scary, too, and we never actually see that either. More than anything, she seems like a surly flight attendant shooing Indy toward the Kingdom of the Crystal Gayles with a sword and an army of expendable minions instead of a beverage cart.

There’s also a Big Mean Guy — a poor man’s Pat Roach — and Mac, Indy’s friend and erstwhile “double/triple/can’t keep track and don’t care” agent. Oh, and lest we forget the skull-wearing, grave-guarding, karate-chopping imps in the cemetery whom decamp as quickly as they appear. (Although I don’t know if they count as bad guys since they seem to be hired more for graveyard ambiance than for actual villainy.) This film is crying out for a decent villain — or at least one with a cool outfit. Let’s contrast, shall we?

Raiders of the Lost Ark – Belloq is the main villain, and the best, for one simple reason: he is Indy’s dark side. “We’re very much alike, you and I,” he says in the Cairo cafe. They pursue the same things with the same passion and the same skill, but Indy has limits, including a distaste for Nazis. Belloq, not so much. As if Indy matching wits against the dark side of his own nature isn’t enough, Raiders has Dietrect and Toht. Dietrich, the German commander, represents the brutish bureaucracy of the Nazi machine: absorbed in schedules, reports and military efficiency. The guy casually tossing Marian inside the Well of Souls could just as easily be standing beside the gas chambers at Auschwitz and ushering in a huddled mass of naked victims. Toht has a cool outfit — remember that possible implement of torture that turns out to be his coat hanger? — but being a sadistic monster helps, too. Marian’s plea that she can “be reasonable” is irrelevant next to his interest in causing pain, but he’s justly repaid by having the headpiece for the Staff of Ra permanently emblazoned on his palm. Together, Belloq, Dietrich and Toht make a very effective triumvirate of villainy, each unique and each interesting.

Temple of Doom – I’ll pass over Lao Che because he’s on screen for less time than it takes to for me to type the title of Indy 4. Mola Ram, the Thugee priest, rips out still-beating hearts and pours coffee out of a human skull. That is a villain. And not a single gray jumpsuit in sight.

Last Crusade – We’ve got the Nazi uber-creep Vogel, who’s basically Raiders’ Dietrich with a bad crack habit. He’s not very original but he’s got some great lines superbly acted, and amping up the crazy eyes is a great way to recycle a villain. Donovan represents a certain disillusionment or jading that seems appropriate at this stage of the film series: a traitor to his country more concerned with personal immortality than patriotism or even reverence for the Holy Grail. Elsa Schneider is a virtual reincarnation of Belloq, but the intrigue of a romance with Indy and the revelation of her Nazi loyalties gives a little freshness to the character. Plus she looks better in a bathrobe.

Issue 4 – Nuking the Fridge

It’s no mere trick of hyperbole that “nuking the fridge” has become synonymous with TV’s turn-of-phrase: “jumping the shark.” The Indiana Jones series has been filled with moments that defy the basic principles of physics. Take the skydiving incident from Temple of Doom: Indy, Willie and Short Round find themselves sans parachutes on a foundering airplane. The only escape is to grab an inflatable raft, jump out of the plane and pull the inflation valve. Your average third-grader can come up with sixteen reasons this doesn’t make any sense — which it doesn’t — but at least, at least we’re treated to a supporting character who’s equally certain this feat is impossible and spends the whole ride screaming her head off.

I’m not saying nuking the fridge wasn’t entertaining to watch, but it stretched the bounds of plausibility way too early and opened the door for the cartoon physics we’re subjected to again and again throughout the rest of the film.

Issue 5 – Indy’s Credulity

To me, this is probably to most offensive misstep of this movie. Skepticism is one of the most prominent, if not THE defining, characteristic of Indiana Jones — a through-line maintained in all of the first three films. In each, Indy dismisses even the possibility of the supernatural until circumstances force him to become a true believer. Crusade uses Dr. Jones’ classroom to illustrate his world view: archaeology, he says, is “the search for fact. Not truth. If it’s truth you’re interested in, Doctor Tyree’s Philosophy class is right down the hall.” (Luckily for Dr. Jones, and us, part of his character arc is finding truth amidst his search for fact: truth about himself, his relationships and his own view of the world.)

According to Indy, the great artifacts of the world “belong in a museum,” not a house of worship. The significance of the world’s found objects is purely cultural and historical, not spiritual. He’s a scientist, an academic. The great dichotomy of the series was the tension between Indy, this man of science, and the various “true believers,” both friend and foe, who forced him to confront his skepticism and revise it as circumstances warrant.

But in Kingdom — when confronted by circumstances that leave audience members already familiar with Independence Day, Men in Black, Alien vs. Predator and dozens of other sci-fi tropes questioning the plausibility of aliens in Indy’s 1957 world — Indy buys it. Lock, stock and magnetic coffin. Maybe it was all that time in the OSS that turned him credulous.

As for me, I just can’t take the leap to aliens; the whole story line feels so out of place in an Indiana Jones film. I should point out that the bad guys became Soviets this time around because the filmmakers felt the three previous films had “plumb wore the Nazis out.” Yes. Lucas and Spielberg thought Nazis were played out but aliens didn’t ring any bells? Do these guys watch their own films or do they have assistants for that?

Issue 6 – That Kid

So Shia LeBeefcake is an “It Boy.” I get it. In the golden days of Hollywood, this guy wouldn’t have made it as Pioneer #3 who gets offed by the Indians in an episode of Wagon Train. Whatever. I’ll accept his status much in the same way that I accept opposition to missile defense shields and other viewpoints that make no sense.

But it doesn’t make this idiot any less annoying.

Lucas and Spielberg claim they wanted to use Mutt as Indy’s foil by portraying him the way Henry Jones Sr. once looked at his son. Fine, except that Henry Jones Sr. doesn’t appear in this movie, so we never really know what that is supposed to mean. What remains is a canned stock character with a bouffant hairdo and a ridiculous nickname. Ooooh, he rides a motorcycle — he must be a rebel!

And if you don’t know Mutt is Indy’s son by the time the previews roll, well. Mensa won’t be calling anytime soon. I’m sorry.

Issue 7 – The Marian Heresy

In the midst of Mutt explaining — and you know how I love that — he hands Indy a letter his mother sent him. This is probably the silliest contrivance of the movie, with the possible exception of the ending. “I’ve known lots of Marys,” says Indy. Apparently forgetting he was a week away from marrying one of them. Please.

Indy’s sitting in the cafe holding a letter written by, as Mutt would tell it, an old friend of his and it doesn’t cross his mind to see if the handwriting looks familiar? After all those years of on-again-off-again romance, in an age before email, text messages, Facebook, cell phones, cheap long distance and Skype, they expect us to believe Marian never once wrote Indy a letter? Made a grocery list? Signed a tax return? Something? Couldn’t they at least have made the note typewritten? Throw us a bone here.

Marian’s introduction in Raiders, on the other hand, was pitch perfect. She drinks a big fat sherpa under the table and then decks Indiana Jones for dessert. She’s not just well-drawn, she is interesting.

Okay, she was interesting. I realize the years have been kinder to Harrison Ford than Karen Allen, but this was the moment for Lucas and Spielberg to invest in some soft focus lenses and then run with it — or at least trust to the audience’s love of the Marian Ravenwood character to forgive Karen Allen for not being a perfect size 6 ingenue anymore. Which we would have. Instead, their solution was to slash her storyline into the utterly unintelligible by allotting her screen time roughly equivalent to that of the giant killer ants. I hope Karen at least got the bigger trailer.

And after, as I’ve said, years of on-again-off-again romance — a romance so dubious Dr. Jones breaks it off one week before the wedding — all that’s required for meaningful reconciliation is a four-minute hostage situation in the back of a truck. A quick admission that Mutt is really Indy’s son and it’s suddenly a Stauffer’s Lasagna commercial. If their relationship was so meant to be, why 20 years of zero contact? No “I tried to find you … I wanted to start over,” no tattered photos or cherished mementos, etc. “Wow, it’s you and I haven’t really missed you or anything but, since we’re both here, what about another go?”

Issue 8 – The Supporting Cast

Ray Winstone, usually a joy to watch, is an empty neckerchief in this. Jim Broadbent appears on screen for maybe 90 seconds and each tick of the clock is excruciating. Then there’s crazy John Hurt. Crazy because, you know, he’s got the long hair and the ratty clothes and he talks in gibberish.

None of these characters matter because, while they lend absolutely nothing to the nonsensical story, they’re also a yawn to watch. Seriously, they could have hired Marcel Marceau to stand in for all three of these characters and it would have been more entertaining. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of Classically Trained British Actors with Nothing to Do.

Issue 9 – Contrived Happy Ending

Unless you’ve adapted a Jane Austen novel, a wedding is a contrived ending. A wedding between two long-separated lovers whose only relational issue seems to be an adult son with a stupid name is an insult to the audience. To stage this wedding in a church with the bride in a white dress instead of on the deck of a tramp steamer chugging up the Amazon just rubs our noses in the filmmakers failure to know their characters at least as well as we do.

Final Thoughts

Despite this mountain of evidence to the contrary, I didn’t hate this movie. There are a lot of cute moments and some good in-jokes. Harrison Ford is still enjoyable to watch.

I just feel disappointment — on par with what you might feel learning that the guy voted “Most Likely to Succeed” when you graduated high school now works the evening shift at Lube Express. You just expected a lot more. And you’d rather have kept your cherished ideal of his fate than to ever have learned the unpoetic truth.

A film character of Indiana Jones’ caliber, embraced by audiences and etched into our culture as he is, carries certain expectations. Characters like Indy can evolve — but changing the rules of his world is a sorry trick. And a waste of many talents.

![]()

[hr]

1 This doesn’t mean there are never occasions when characters can explain something or the main character is in the dark. But it’s a very weak way to begin a film. Successful expository dialogue usual comes after we’ve had a chance to see the major characters in action and then ask: “Why is he/why is she/why are they doing this?” After we get to know and like the main character then we can be presented with a mysterious problem that requires explanation, usually to a symbolic novice: the inexperienced farmboy, the green recruit, someone who we expect to be clueless. For example, Little Miss Sunshine opens with Frank (Steve Carrell) in the hospital after a failed suicide attempt. After Frank moves in with his sister and her family, there’s a dinner scene in which Olive (Abigail Breslin), Frank’s seven-year-old niece, asks about his bandages. Frank’s explanation for the suicide attempt, offset by various interjections of his family, illuminates both Frank’s backstory and each character at the table. But we don’t reach this moment until we’ve already had at least one scene with each member of the family and established some expectations of who they are so that it feels less like exposition and more like reinforcement.

Leslie Loftis (@LeslieLoftisTX) says

Okay, this is old. But I don’t care. It is lovely. You didn’t happen to do The Force Awakens or any of the franchise failures in between. (Or do I know you by another name on other websites?)

So glad you found me on twitter. Already shared your marriage post. Look forward to reading more.